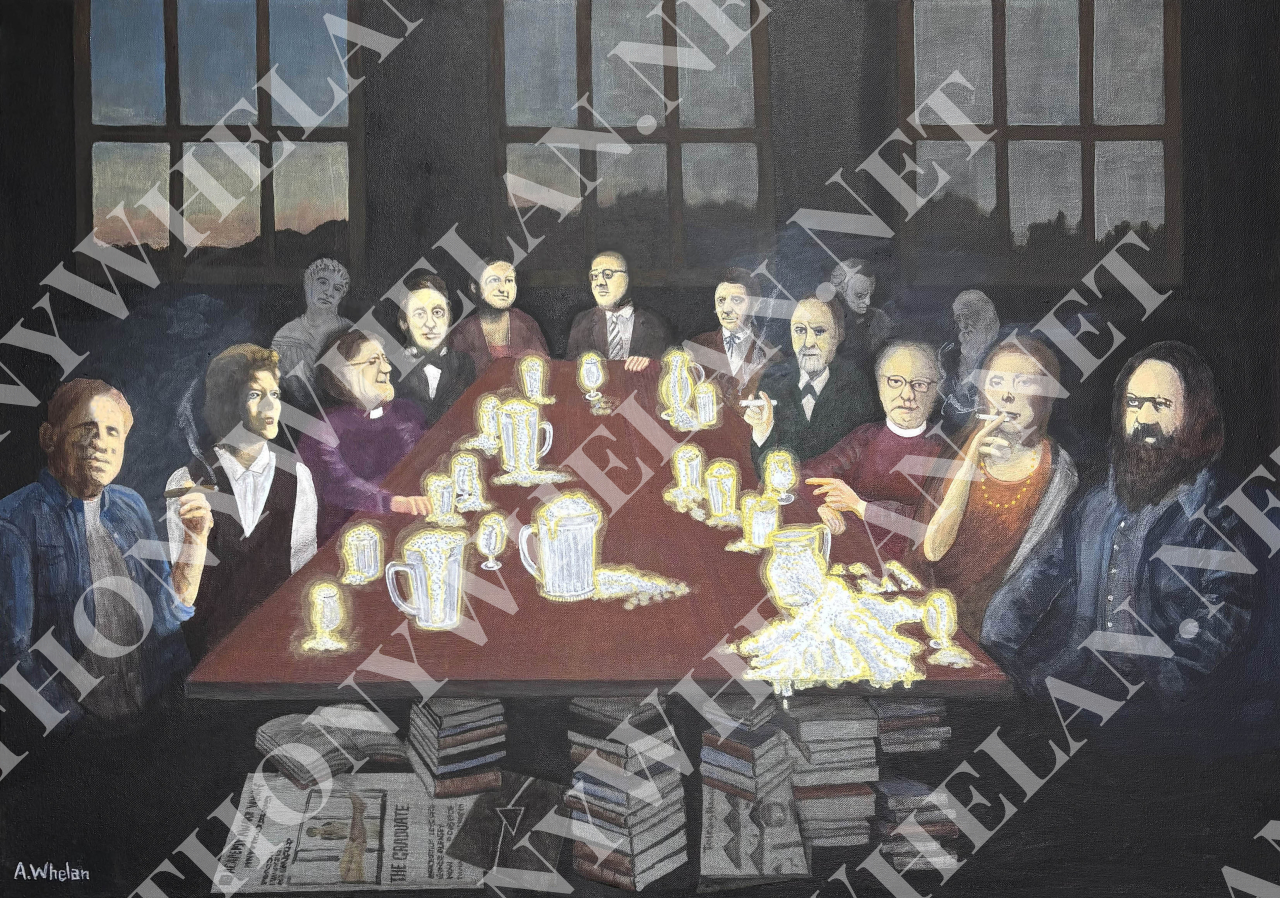

This painting was conceived as an exploration—albeit to some extent—of how certain individuals and the movements they initiated, supported, or championed, have influenced generations over time.

Understanding the mechanisms of influence within Western society is a major theme in my book The Tide Has Turned. However, this artwork does not encapsulate the entire book but rather the sections that address cultural shifts in Britain, the broader Western world, and within the Church.

In contemporary digital culture, we often hear of social media "influencers," but their impact is largely superficial. The deeper, more profound influences shaping today's society and culture originate elsewhere.

The painting's working title was The Influencers. I also considered The Last Day’s Supper, The Last Intellectual Supper, The Spectre of Conversation, and A Symposium of Shadows—titles reflecting the interplay between dialogue, intellect, and illusion. Ultimately, I settled on The Foam of Discourse. The motif of foam was inspired by a quote from one of the figures seated at the table: American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson, who once said, "We sip the foam of many lives."

The figures depicted are not included solely for their individual identities but for the broader groups, movements, ideas, and ideologies they represent. Some of them, particularly Terry Virgo and, to a lesser extent, Archbishop Robert Runcie are motifs (see below).

The Figures at the Table

Proceeding clockwise from the left, we begin with the man smoking a cigar: Herbert Marcuse. A leading figure in Cultural Marxism, he was instrumental in the ideological developments I discuss extensively in The Tide Has Turned. He was a contemporary of Theodor Adorno, seated at the head of the table. Marcuse and Adorno, along with other key thinkers, propagated neo-Marxist ideas from the 1920s onward, laying the groundwork for the sexual revolution of the 1960s. Marcuse is seated opposite Karl Marx, the founder of what we now term Classical Marxism.

Next is David Bowie, representing the major figures of the rock and pop music industry of the 1960s and 1970s. His influence, particularly in the areas of gender fluidity and youth rebellion, is explored in the book. Across from him sits Joni Mitchell, another highly influential singer-songwriter of that period.

Beside Bowie is Terry Virgo, a key leader of the House Church movement in the UK during the 1970s and 1980s. This movement sought to revitalise Christianity at a time when traditional churches were in decline, distancing itself from denominational structures it perceived as rigid. This representation of Virgo is displayed as a motif.

A motif is a repeated element that appears in a work of art, literature, or music to reinforce a theme, add depth. While a motif can be symbolic, it is primarily defined by its recurrence. You will find a similar character in a later painting, The Sleeping Bride.

Virgo sits opposite Archbishop Robert Runcie, a leader in the established church around the same time. Their similar attire symbolises the eventual resemblance of the "New Churches" to the hierarchical institutions they initially opposed. Though the newer movements rejected clerical vestments, they ultimately reinstated a similar authority structure. The ‘new’ churches may not have taken to wearing the clerical garb, but they have slipped back into the old churches’ practice of positioning and presenting a vicar-like figure; a leader who exudes unassailable authority and wears it like a clerical collar.

Next is Henry David Thoreau, the American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. Seated opposite Emerson, Thoreau introduced environmentalist and transcendentalist ideas into Western culture. His book Walden – Life in the Woods, recounts a period of simple living in natural surroundings, while his essay Civil Disobedience was a key influence on the countercultural movements of the 1960s. His famous quote—"The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation"—was later adapted by Pink Floyd on their album Dark Side of the Moon (1973), critiquing British societal restraint. They said that hanging on to a life of quiet desperation is a particularly English thing.

Following Thoreau is Alice Bailey, a founder of the New Age movement. Over three decades, she wrote extensively about her vision for a new world order, advocating for sexual liberation, abortion rights, the breakdown of the traditional family, and the erosion of Christianity. She claimed to have channelled much of her work through a "Tibetan teacher" named Djwhal Khul, whom she regarded as a spiritual guide but who, from a Christian perspective, could be considered a demonic entity. In The Tide Has Turned I wrote about how many today believe that New Age beliefs are defunct but argue that they are alive and well, and living under a different name.

Next is Theodor Adorno, already mentioned as a central figure in neo-Marxist thought. He and his colleagues developed Critical Theory—a tool for dismantling Western culture, particularly its Judeo-Christian foundations, through relentless critique and subversion.

At the top right of the table sits Ralph Waldo Emerson, a leading figure of the 19th-century Transcendentalist movement.

Beside him is Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. Freud revolutionised the understanding of human psychology, particularly in relation to sexuality, and his ideas contributed to an enduring cultural preoccupation with the self—an influence still evident in contemporary worship music and personal testimonies within churches.

Archbishop Robert Runcie, previously identified, represents not only himself but numerous church leaders who have, over time, diluted or abandoned fundamental Christian doctrines. (We might consider his appearance here, as with others, a type of motif). Many bishops and archbishops within traditional denominations, particularly the Church of England, have contributed to the erosion of biblical authority.

Next to Runcie is Joni Mitchell. Her song Woodstock romanticised the 1969 festival, a landmark event for the hippie counterculture, celebrating ideals of peace, love, and unrestrained freedom—ideologies that align with the broader New Age movement.

Finally, Karl Marx is seated at the table, representing the foundational ideology of Communism and Marxism. His theories have incited rebellion, revolution—often violent—and widespread societal upheaval.

The Ghostly Figures

Behind the table stand shadowy figures who have influenced the thinkers below.

On the left is Constantine the Great, Roman Emperor from AD 306–337. His apparent conversion to Christianity elevated the faith within the empire, yet his actions led to the systemic persecution of Jews. He distanced Christianity from its Jewish roots, a legacy that persists in Christian thought today through Replacement Theology (or Fulfilment Theology), which denies the ongoing significance of the Jewish people in God's plan.

On the top right is Immanuel Kant, a leading Enlightenment thinker. The Enlightenment, spanning the 17th to 19th centuries, radically transformed Western philosophy, science, politics, and religion. Though it introduced certain intellectual advancements, it also undermined the foundations of faith. Kant, positioned above Runcie, signifies his influence on religious leaders who increasingly embraced scepticism.

Beside Kant hovers Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution challenged the biblical creation narrative, leading many church leaders to question Scripture’s reliability.

Cultural Artefacts and Lighting

Beneath the table lie cultural artefacts—books, magazines, films, and music—through which these figures' ideologies were disseminated, particularly to younger generations.

Notably, the faces at the table are illuminated—not by visible light sources such as candles or electricity, but by the glowing foam in their glasses and jugs. This glow represents their thoughts, ideas, and philosophies—fleeting and destined to fade.

(A motif, in art, literature or music, is a recurring element that reinforces a theme and adds depth. Though symbolic, its defining quality is repetition. A similar figure appears in a later painting, 'The Sleeping Bride').